State of Linux Gaming

Linux is the dominant server hosting operating system, but it falls short when it comes to desktop users. The Linux community can complain all day about how unfair the competition is, and it’s true, Linux is mostly maintained by open-source programmers and non-profits, yet they are attempting to compete against a multi-trillion-dollar tech giant, Microsoft. But at the end of the day, people will switch to Linux when it’s accessible enough, when their games and software all “just work.” For decades, gamers could not justify the switch since few games would run on it. This all started taking a major shift when Valve began working on Proton, a compatibility layer that enables Windows games to run on Linux based on the open-source tool Wine.

Since its launch in 2018, Proton has grown to allow Linux to be a viable option for many gamers. Doubling down, Valve released the Steam Deck, a portable handheld gaming device that runs on a customized version of Arch Linux. Currently the vast majority of the most popular games run great on Linux.

This seems great for gamers, the Linux community, Valve, and the game developers. Studios no longer need to dedicate teams of programmers to maintain a Linux version that hardly anyone plays. But recently, game publishers such as EA, Epic, Ubisoft, Riot, and more have taken a harsh stance, barring those who use Linux from enjoying their games through kernel-level anti-cheat requirements that aren’t compatible with Linux.

The anti-cheat developers are justifiably quiet about their tools. Any information they reveal may be used by cheat creators to give themselves an advantage. Every year, major competitive games announce updates to their fair play systems. But often, it’s just marketing fluff. They want to please players and make them think there will be fewer rule-breakers. The reality is, we attain minuscule information on what has been done unless they’ve implemented major, bulletproof deterrents or included changes that affect regular players, like banning mice or requiring a unique phone number to play.

Do Linux players cheat more? It seems obvious given the number of competitive games that have banned Linux, but I don’t believe so. To grasp my reasoning, you’ll need a high-level overview of how these cheats function and some background on the decades-long cat-and-mouse game between game developers and game manipulators.

Kernel Level Anti-Cheat

How Cheats Work

Most cheats work by monitoring and/or modifying the memory used by a game. Imagine computer’s memory as a massive grid with billions of cells, each with a unique address. When launching a game, it allocates a chunk of this canvas to store the necessary variables. Somewhere within that section will be the values associated with character’s health, stamina, position, ammo count, etc. This also includes data for other players and NPCs. Hackers just need to keep track of which address has which values and then create a fairly simple tool to adjust the values at those addresses. This was, of course, simplified, but it may be surprising to see how simple it is to execute. I won’t link it here, but a simple online search of “how to use Cheat Engine in [your favorite single-player game here]”, and there will likely be an easy-to-follow tutorial.

This is where the arms race begins. Adjusting a player’s health from 100 to 1000 in an online game is detectable and preventable by the server. Game servers are able to keep track of invalid changes, making most major cheats essentially impossible.

Because of this, modern cheats tend to use memory values to give “extra sensory perceptions,” also known as ESP. The most common one is finding the enemy player positions in memory and displaying an overlay to allow the exploiters to see people through walls.

What is the Kernel?

The kernel is the gatekeeper between the software and the computer’s hardware. As mentioned earlier, when a game runs, it is allocated a chunk of memory. This allocated space is requested by the application from the kernel. The kernel also has the ability to block any other software from accessing memory outside of its allocated space. For Windows, running software as administrator allows it to access other software memory, but importantly, this is not a bypass; the kernel is simply allowing it due to its virtual “Administrator” status.

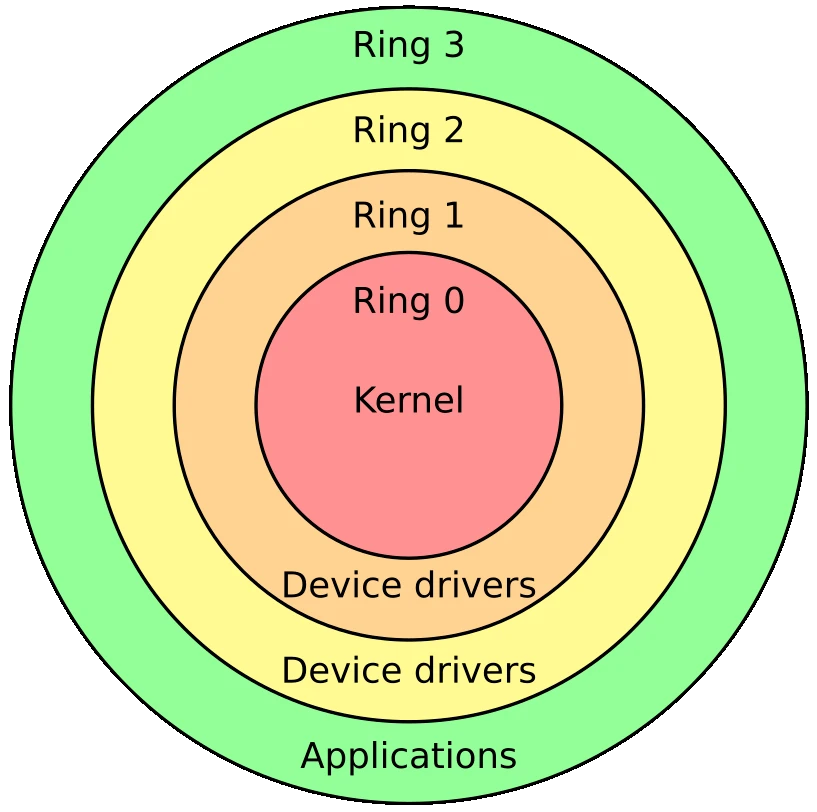

But we aren’t talking about kernel anti-cheat; we are talking about kernel-level anti-cheat. This implies the the cheat prevention system is running at the same privilege level as the kernel, meaning it has the same level of access and control. In computer architecture this level is called “Ring 0,” and the user space is “Ring 3.”

Source: Protection Ring Wikipedia

How Kernel-Level Anti-Cheat Works

The reason for kernel-level anti-cheat should be fairly obvious. Hackers access and modify the memory of games to their advantage, and the kernel gatekeeps the memory. Kernel-level anti-cheat prevents any unknown software from modifying the memory associated with the game.

Bypassing Kernel-Level Anti-Cheat

Anyone who’s extensively played an online multiplayer game or just pays attention to the community, will know that kernel-level anti-cheat is not perfect. Hackers are still able to bypass it, but how?

As previously mentioned, this is the developer versus cheater arms race.

It’s a back and forth that could be explained for hours, but I will summarize. Those seeking an unfair advantage can just run their cheats at the kernel level as well. That worked for the most part until Secure Boot was standardized, which only allows authorized firmware to run on the kernel. This means hackers require Microsoft’s team to approve their cheat and pay up to $1000 annually for an “Extended Validation” certificate. Something that likely won’t happen. Disabling secure boot is detectable, and enabling test-signing for drivers is also detectable.

This is where the difference between Windows and Linux lies. Linux does not have an equivalent certificate system nor the team to ensure no malicious software receives a signature. When considering all of this and the low market share of Linux gamers, preventing them from engaging in the competitive multiplayer game space seems like the obvious choice.

Information on exactly how to bypass anti-cheat is a bit difficult to come by, and I can’t say for certain how any cheat works, but there seem to be a couple of primary strategies. The first is finding old signed and certified drivers that have had vulnerabilities in them. These drivers typically get patched, but the old ones are still valid and can pass the secure boot checks. More often than not, these vulnerabilities allow hackers to utilize the driver to execute their own code. I suspect this is the most common strategy because of its asymmetric effort. It’s one that can be consistently done for any game, but there’s no simple way to block it with game integrity software. Another option is to run the game in a virtual environment where they can trick the game into thinking secure boot is enabled while still running their drivers. It’s nearly impossible to make a perfect virtual environment; there are always detectable patterns that cheat detection software look for. Additionally, the TPM 2.0 requirement to launch games like Valorant makes it seemingly impossible to develop exploits, but again, it’s an arms race, hackers are always slipping past the barricades.

Linux Players Are Not Cheating

Cheaters have always existed, and the advancement of anti-cheat has not changed this. In fact, a quick search online to find cheats for any multiplayer games, shows there are plenty of online marketplaces to purchase them. They typically run for a few dollars a day or around $50-$100 a month.

To be clear, I do not endorse cheating in online competitive games, nor is it legal in many cases, nor is it ethical.

The validity of these online cheat markets is iffy, and without purchasing and testing cheats for myself, I can’t know for certain how legitimate they are. With that said, many of these companies have faced legal repercussions from the game studios taking legal action against them. This is enough evidence to prove that at least some of these online marketplaces exist, and they all have similar pricing.

What I cannot find are any cheats for Linux that aren’t just proof-of-concept open-source cheats for games that lack anti-cheats to begin with. Additionally, many of the most popular tools for making these cheats, such as Cheat Engine, are missing Linux versions. There are Linux alternatives, but at this point Cheat Engine is a standard tool for game hackers. It’s common to find Cheat Engine “tables,” which are Cheat Engine files for specific games that usually include the common memory addresses for things like player health and level.

To give the development teams the benefit of the doubt, maybe the Linux community (known for their commitment to open source) are just very secretive about distributing their cheats. Or maybe the average Linux enthusiast is just a talented hacker that makes cheats for themselves. But neither of these makes sense, especially considering the Linux gaming user base makes up a few percent of the PC gamers at best(most of whom are Steam Decks).

The price of cheats is likely determined by a variety of factors; the three specific ones are

- Pricing them high enough so there are fewer people using their cheats, making it harder to detect.

- The difficulty of creating the cheats.

- Competitive pricing.

What I noticed is that the price of cheats for games such as The Finals, Counter-Strike, War Thunder, and Hunt Showdown, all games that allow Linux players, were no cheaper than the cheats for games like Valorant, Apex Legends, and Fortnite that explicitly denied Linux access.

The methods used to create these cheats in games like Valorant are likely the same methods used to create them in The Finals and Counter-Strike due to the similar pricing, demand, and similarities in their capabilities. An engineer with the skill to create an exploit that works on a game like Valorant, will be able to reuse the work and code on games with less intrusive cheat prevention solutions.

There’s a term, “security through superior targetability,” that we sometimes understand intuitively. It’s often explained with the joke about two hikers and a bear: you don’t need to outrun the bear, just your friend. This doesn’t work in video games because cheaters aren’t simply trying to cheat at any video game; they don’t just look for the easiest target. They want to cheat at the specific game they enjoy. This is well researched and explained in books such as Consalvo’s “Cheating: Gaining Advantage in Videogames” (2007). Anti-cheat creators can’t just “outrun” their competition. They need to be able to stop and enforce cheating.

“A lock does no more than keep an honest man, honest.” - Robin Hobb

There are easily accessible cheats (often called scripting). By the time an anti-cheat is proficient at detecting and enforce scripting, it’s no longer dealing with regular players who got a little curious or frustrated. It’s dealing with cheaters.

The main difference between cheating on Windows and Linux is the driver certification process. By banning the Linux community, these companies are essentially stating that there’s a substantial enough group of people who know how to create and distribute ring-0 cheats that slip past all the checks of their kernel-level anti-cheats, but these people are not capable of visiting a site like loldrivers.io, and using one of these vulnerable drivers to bridge their cheats. That group of people is large enough to make it worth banning Microsoft’s only competition in the operating system market.

Why Companies Are Blaming Linux Users

I’ve already explained this, but if we trust what they are saying, it’s because Linux provides an easier option for cheating since they can bypass the secure certification process enforced by Windows. I have a difficult time believing this because the released data is iffy. The best thing EA gave us regarding Apex Legends was from this tweet where they showed a declining chart representing “infected matches” with an unlabeled Y axis. And as mentioned earlier, I could not find a single marketplace that includes Linux cheats.

I believe the real reason for preventing Linux players is a combination of factors:

First is that Linux is an easier platform to cheat on, and it only makes up a small fraction of players. When tasked with creating an cheat prevention solution, Linux appears to be the lowest-hanging fruit.

Second is the cost of maintaining a Linux version of anti-cheat. Valve’s compatibility layer, Proton, does not emulate the Windows kernel (this is why cheats for Windows do not work on Linux); therefore, custom cheat prevention solutions need a Linux version. It’s worth noting Easy Anti-Cheat, BattlEye, Valve Anti-Cheat, and PunkBuster all have Linux versions. These make up most of the market’s anti-cheat solutions. At the time of writing this, the top 10 games on Steam all use an anti-cheat that’s compatible with Linux, but 4 of them (PUBG, Apex Legends, Rust, and GTA 5) block it.

Lastly, public perspective. Anti-cheat is addressed often by developers, and I assume this is due to the pushback from the players. Telling their community they have increased the effectiveness of their anti-cheat is going to almost always be seen as a good thing by their community.

I do want to be more charitable to the teams and decision-makers working on these anti-cheats. There are a few potential security concerns regarding Linux. For one, different distributions of Linux rely on different kernel versions and configurations, making it more difficult to create security guarantees. Additionally, many anti-cheats rely on detecting patterns between users. This is called signature detection or signature scanning. When a user is found to be cheating, they can find similar software actions on other people’s devices to find more people using the same cheats. With Linux having a much lower market share, this makes one of the most common anti-cheat techniques less efficient. Lastly, if a game only has 1% of its users coming from Linux, it’s not that unbelievable to think that it has over 1% of its cheaters, making it a positive return on investment, though I do believe this is misguided.

Solutions

Although I believe that turning on Linux’s anti-cheat software would have a minimal effect on cheating rates. This stalemate between Linux gamers and game developers, however, could be resolved in a number of ways.

Pressure from the Market

Natural market pressure is already being created by the rising popularity of the Steam Deck and Valve’s official release of their Linux-based OS, SteamOS, as well as the growing number of Windows users switching to Linux, as reported by the Steam Hardware Survey. With tech influencers like SomeOrdinaryGamer, PewDiePie, and Linus Tech Tips promoting Linux and the increasing dissatisfaction with Windows (Forced updates, recall feature, and ads in the start menu), the cost-benefit analysis for studios will unavoidably change.

We should look for ways to accelerate this process. Ultimately, a Linux player base that would give more money to these companies than it costs to support it would be enough to get the game developers on board.

Standardized Security Framework for Linux Gaming

It may seem counter to Linux’s philosophy of freedom and choice, but a standardized security framework specifically for gaming could address publishers’ concerns. Valve is uniquely positioned to lead this effort with their investments in Proton, SteamOS, and their collaboration with Arch Linux.

This wouldn’t necessarily require a full Windows-style certification system, but rather a more targeted approach:

- A gaming-specific secure runtime environment that provides anti-cheat developers standardized APIs for monitoring game integrity.

- A certification process for anti-cheat modules that verifies they will not compromise system stability or security.

- A common framework across major distributions that ensures anti-cheat functionality works consistently.

Importantly, this could be implemented as an opt-in system that preserves user choice; gamers who want to play these competitive titles could enable the secure gaming environment, while those concerned about privacy could simply choose not to play those specific games.

Enhanced Server-Side Detection

Server-side anti-cheat solutions deserve more investment and attention. Recent advances in behavioral analysis and machine learning could significantly improve their effectiveness without requiring invasive client-side access.

Games like Counter-Strike 2 and Dota 2 already rely heavily on server-side verification and behavioral analysis to detect rule-breakers. Valve’s VACnet uses deep learning to analyze player behavior patterns and identify cheats with increasing accuracy. This approach is inherently platform-agnostic and doesn’t require root-level access to players’ systems.

With the massive amounts of gameplay data available and improvements in AI, developers could build more sophisticated behavioral models that detect abnormal play patterns, implement server-side verification for player actions that would make many common cheats ineffective, and use replay analysis to retroactively identify and ban exploiters based on their gameplay.

Community-Driven Solutions

The Linux gaming community itself could take more proactive steps: instead of individual complaints, organizing coordinated campaigns to engage developers with data-driven arguments about the Linux market’s growth and potential. The Linux community could also create clear guides for development teams on how to implement their anti-cheat solutions on Linux. The Linux community should also praise studios that allow Linux gamers to participate in multiplayer games such as The Finals (Embark), Counter-Strike 2 (Valve), Overwatch 2 (Blizzard), Deadlock (Valve), Hunt: Showdown (Crytek), Dead by Daylight (Behaviour Interactive Inc.), and many more.

Transparency from Game Developers

Game developers should be encouraged to provide more transparency about their anti-cheat decisions. If Linux is truly a platform that enables more cheating, game companies should share anonymized data supporting this claim. This would allow the Linux community to address specific security concerns rather than being left in the dark.

Several game studios have already demonstrated that supporting Linux doesn’t compromise their anti-cheat effectiveness. Games like The Finals, Counter-Strike, and War Thunder all use anti-cheat that works with Linux. Documentation of their implementation approaches could serve as a blueprint for other developers.

Ultimately, the solution will require collaboration between the Linux community, game developers, and platform holders like Valve. With the right approach, anti-cheat compatibility doesn’t need to be a barrier to Linux gaming adoption but rather just another technical challenge to overcome in the evolution of gaming platforms.

Why It’s Important

The decision to allow a piece of software to run at the kernel level should not be taken lightly; especially one that is updated frequently like an anti-cheat. The kernel is a extremely important and fragile component to an operating system. If you’ve ever experienced a Blue Screen of Death you’ve likely experienced an error in a kernel level driver. When a driver fails, which can happen with something as simple as attempting to divide by zero and not handling the exception, the solution is to display a blue screen and reboot the computer; it’s a fail safe.

If a driver, for whatever reason, errors on startup, they can prevent the OS from booting. This happened on a large scale recently with cyber security company, CrowdStrike that caused millions of computers to fail to boot. There isn’t anything stopping the same thing from happening to kernel level anti-cheats. Additionally, as mentioned earlier, there are a ton of driver that are vulnerable to privilege escalation attacks which are used to make the cheats. Normally, the concern with vulnerable drivers is it could allow hackers full access to the victims computer. If a vulnerability like that was found with a kernel level anti-cheat most PC gamers would be at risk. It may have happened recently at an Apex Legends Tournament, but it is denied by EA. Other kernel level anti-cheats have had vulnerabilities reported.

Window’s Monopoly

This goes way beyond whether someone can play Apex Legends on their Steam Deck. Microsoft has basically had a monopoly on PC gaming for decades. “PC gaming” has become another way to say “Windows gaming.” No matter how much someone might prefer Linux for privacy, security, or philosophical reasons, they’re stuck with Windows if they want to play the more popular competitive games.

Proton is the first real challenge to this monopoly in forever. When game studios block Linux through anti-cheat decisions, they’re not just annoying a small percentage of players; they’re helping keep a monopolistic market structure in place that affects everyone.

Windows 11 has become more and more intrusive and annoying. They’ve increased data collection, ads, and added a ton of AI features randomly scattered throughout the OS. For gamers, there is no real alternative; we must deal with it. If there was some competition from Linux, that could force Windows to actually address user concerns regarding privacy, control, and performance.

PC gamers are more often than not, tech enthusiasts. PCs are just harder to use than consoles. If Linux had equal access to the gaming library of Windows, gamers would likely be early adopters and help Linux reach a critical mass. By blocking anti-cheat on Linux, the studios are unintentionally assisting Microsoft maintain their monopoly.

Security

Kernel-level anti-cheats are changing how we view computer ownership. Traditionally, users have had full control over their own hardware and software. Installing a kernel-level anti-cheat gives some corporation privileged access to monitor and control your system.

If we accept that game companies can demand system-level access, other software companies will make similar demands. This normalization could completely change the relationship between us and our computers, making them monitoring systems for corporations.

Conclusion

Valve and the communities’ work on Proton has allowed us to reach a point where nearly every PC game can technically run on Linux, but the anti-cheat restrictions keep holding back Linux. We shouldn’t just look at this as a niche issue for the small group of arrogant Linux nerds. We shouldn’t respond with, “just use Windows”. It’s part of a bigger problem regarding the future of personal ownership, freedom, and market competition.

Game developers and players obviously care about stopping cheaters, but the evidence suggests that blocking open-source OS users is more about saving development resources and avoiding risk than actual security benefits. This decision doesn’t just exclude a small percentage of potential players; it helps maintain an operating system monopoly that affects all PC users.

We should demand more transparency regarding anti-cheat information and push for solutions that balance competitive integrity with platform openness. Being able to choose our operating system is worth protecting, even if it means developers need to put in extra work.